– Autonomous organizing is not one-size-fits-all, and for this reason, we must analyze the IE’s unique material, geographical, historical, and demographic conditions to center our unique struggles and find methods of resistance that can liberate us accordingly.

The preceding blog post in this series explored the intersections between uprisings in the outskirts, the urgency of organizing in overlooked racialized regions, and parallels between the material conditions in the Inland Empire and Ferguson, Missouri, home of one of the largest insurrections of the 21st Century. This post will explore the new forms of autonomous organizing that can potentially arise from non-urban regions like the Inland Empire. This post argues that we must pay special attention to the intersections of race, lived experience, material conditions, geographic specificity, and class to appropriately experiment with autonomous methods crafted specifically for unique places and contexts.

The state of California is a unique place for many reasons. Unfortunately, history has taught us that California’s most unique trait is that this state is the literal laboratory for American empire to test out new mechanisms of oppression. California is full of examples of attempts to implement stronger forms of racism, refine police tactics of repression, among other advances in the science of population governance. It has accomplished these things primarily through its manipulation and shaping of space and land. Specifically, these are spatially-based solutions to perceived or crafted crises. In other words, this state has historically controlled BIPOC populations via territory, such as (but not limited to) its creation of the following: racist state technologies of power, segregation, redlining, prisons, policing, environmental racism, gentrification, border militarization, and so on. California is the testing lab for improving the operations of this American machine; it is the birthplace of what we now recognize as SWAT teams, created in the first place to repress revolutionary Black organizing in the 1960s. These advances in repression-via-territory are first piloted and beta-tested in the poorest and predominantly BIPOC areas or regions, and then spread everywhere else.

The Inland Empire, likewise, has been the battleground for new forms of racial capitalism, such that the IE has literally become a key part of the infrastructural backbone of the entire United States. We will continue to elaborate on these arguments in other blog pieces, but basically, the IE plays an essential role in the actual logistics of this empire through its distribution, transportation, storage, and production of commodities. However, the IE has not always had to play this significant economic role for the rest of the US. Those who govern the state, capitalists, and other planners collectively created and shaped a new, emergent form of capitalism in the 1980s onward; a new, logistical racial capitalism in the region known as the IE. This coincided with many global capitalist restructurings, migratory patterns, and changes in racial demographics that have given the IE’s BIPOC communities their primarily working-class characteristics. The logistical racial capitalism that has only recently been birthed in this region is the beginning of a new state solution, one aimed to more efficiently govern and discipline the people in the IE.

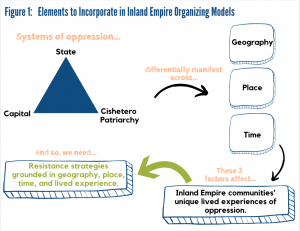

This brings us back to the possibilities of autonomous organizing in a place like the IE. We should center indigenous resurgence and Black liberation as the main goals of our autonomous movements and analyze the possibilities of their attainment. However, autonomous organizing methods are not a one-size-fits-all formula or program. For example, we can see the shortcomings of urban-centric forms of organizing and the organizing done in white-dominant spaces for their inability to effectively translate into different environments and with different communities. We must not assume homogeneity in the ways that racial capitalism, the state, patriarchy, etc. have gripped different spatial landscapes and regions. For these reasons, we should shape and transform our organizing methods to best suit the particular contexts we find ourselves in.

Similar to how we must contextualize organizing based on unique geographies and material conditions, we must also de-universalize Eurocentric notions of liberation and freedom. This is not about forcing ourselves to fit the mold of conventional (i.e. urban-centric and white-dominant) organizing but rather, centering ourselves, our stories, and our experiences first by using autonomy as a blueprint that can be applied to unique contexts. By situating our struggle in Black, Indigenous, and subaltern ways of knowing and experiencing racial capitalism and the state, we can understand the necessary forms of resistance that will be based on our firsthand, lived realities. Who else can better understand how to get free than those who are directly oppressed?