We are writing this piece with the goal of cultivating transparency in our spaces as well as building towards the normalization of accountability, transformative justice, and security culture among our peers. Gatekeeping our comrades, our spaces, and our movements is good, actually – if it means keeping ourselves protected from abusers, grifters, and other forms of harm and co-optation. This piece was compiled and written by several collectives and individuals across the so-called Inland Empire.

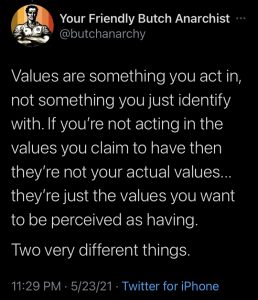

In recent years, more and more comrades have been standing up against the inter-generational problems of abuse and harm within movement spaces. The visibility of such positions against patriarchal harm and intra-community violence are not new, as they have plagued social movements around the world for decades. Black queer and trans feminists have spoken up about these issues for decades now. However, these recent hot-button discussions raise the ultimate question: What do we “owe” each other as comrades? We believe that answer is reciprocity and mutual accountability to each other – and ourselves – as people in a shared, collective struggle. As comrades, we must always be receptive to feedback and constructive criticism; otherwise, we endlessly reproduce cycles of harm and violence in the same spaces that purport to cultivate liberation. This cannot be emphasized enough: the outcome of our struggles is dependent on the strength of our interpersonal dynamics and our commitment to challenging oppression at every turn. Shitty relationships will only ever (re)create shitty politics. It’s time to take seriously incidents of harm and abuse not only because our movements crucially depend on this, but because all we have is each other. We owe it to each other to be responsive in the face of harm. Rather than ignoring community incidents of harm and conflict, we want to learn from them in order to prevent burn-out and violence in our spaces. By revealing repeated behaviors and patterns across various incidents, we hope that folks will feel more able to challenge them. We will discuss recent incidents within our IE context.

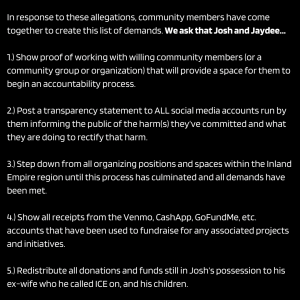

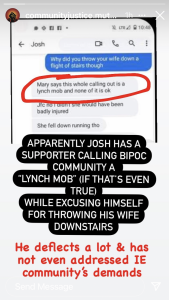

Recently, some allegations against organizers Josh and Jaydee were brought to light and have sparked a lot of conversation. They were called out for stealing donations meant for “mutual aid” projects they were in charge of and using the funds to purchase things for themselves, including an apartment in Orange County. The call out also mentioned that Josh was abusive towards an ex-wife and called ICE on her. This is the list of demands created by community members who drafted the call out statement:

After the call out and demands were posted and Josh and Jaydee had seen them, the community was met with…

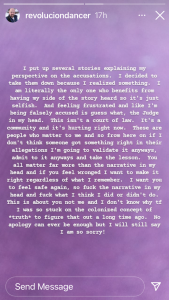

1. A short statement from Josh on his Instagram story (which disappeared after 24 hours and did not acknowledge specific accusations OR the demands made) and then, radio silence. This is a screenshot of Josh’s Instagram apology in response to the call out:

Not pictured is the brief statement saying that “accountability will be coming soon,” which Josh posted to his Instagram grid and later deleted entirely. No remnants of the call out or his response to it can be found on his social media, although he has resumed posting as usual.

2. A dizzying flurry of videos of Jaydee crying – literally – about personal traumas (we will not post those videos), and overall deflection of both the accusations made in the call out as well as the list of demands.

Not included in that call out are BOTH Josh and Jaydee’s white saviorism, tendency to center themselves, disregard for security culture, and general use of “activism” for clout. In fact, they have previously been called in by their peers and asked to step down from organizing due to the harm they’ve caused in these spaces. These conversations happened behind closed doors and were spread among affinity groups before the “call out.”

Multiple people have observed Josh and Jaydee posit themselves as white saviors. In fact, Jaydee’s poetry has been called to question by Black and brown organizers several times for having savior themes and she has been accused of acting like a savior in general. In fact, Jaydee inserted herself into a closed situation when members of a harm reduction group in the area created a fundraiser to help some friends that were close to the group. She contacted the group via social media asking if it was okay for her to fundraise for the situation on her own, despite her not personally knowing the folks that the fundraiser was for and barely knowing members of the group itself. After being told that it was sensitive and that they did not want people outside of it to repost, Jaydee created her own post anyway with her own commentary about the situation – which she had no knowledge about – and even included details that were incorrect. Any funds for that were never seen by the group that originally organized the fundraiser.

Jaydee herself has said on her personal Instagram account and to other organizers that she can’t step down from organizing because it helps her “heal others and heal herself.” In one of her many recent crying videos, she assigns herself the title of “healer” because she works with herbs, as if this must mean she’s incapable of causing harm to the people around her. In these “apology” videos, she gave examples of her organizing experience as if to prove that being an organizer means she can’t cause harm. If this were the case, then no one who’s ever done anything good can ever do anything bad, which is obviously untrue despite how often abuse sympathizers and the like use this rhetoric.

If the community you are trying so hard to “heal” is explicitly telling you that they don’t need your help and that you are actually causing more harm than good, why are you here? Jaydee has made it clear that organizing is a personal venture instead of one that prioritizes true solidarity with community members. In her videos, she made vague statements about “doing the work” to heal and hold herself accountable, but never once specified actual steps she was taking to stop harming the community, except for a mention of “shadow work,” as if personal spirituality will absolve her of the harm she caused.

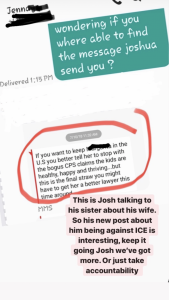

Josh in particular tends to appoint himself as leader and then cause harm that he never takes accountability for. When he initially began working with Riverside Food Not Bombs over a year ago, he made social media accounts for the organization without asking for consent from the rest of the group, then essentially forced a church that he was connected to to be their distribution site, again pushing himself into a position of power. He also discussed possible illegal actions in the organization’s group chat without consent and was angered when asked not to, for the sake of security. It is interesting that he claims to be a seasoned anarchist organizer with such disregard for security culture and horizontal organization. That he jumps at any role involving power over others is not surprising now that it’s public news that he has been abusive in at least one intimate relationship. Even if we were apologists – which we aren’t – nobody can argue with the fact that Josh called ICE on a previous partner and later threatened to call ICE on her again, showing that this was not a one-time incident that he learned from.

Taking a page from the classic Abuse 101 Manual, he accused people of “canceling him” and cried about it to anyone who would hear him, as if public outcry in response to his own actions is anyone’s fault but his. He seemingly fell off the face of the earth for a week or so after he was called out, then deleted the only post he made in response to his call out and resumed business as usual. He posted something about being neurodivergent to his grid, again without ever publicly responding to the call out, seemingly to deflect from the real issue at hand which is the harm he’s caused his ex-wife and his community.

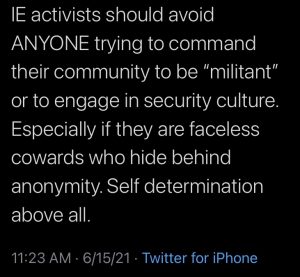

In addition to harm/abuse playbook tactics demonstrated by the two people above, there is another individual in the IE who reveals other common patterns and tactics used by people who try to dodge accountability for their actions. He was previously called in and then publicly called out for being misogynistic towards femme organizers and for being a security threat to himself and others, to no avail of course. He refused to take accountability for his actions or engage in a transformative process with any of the people he harmed or had conflict with last year, yet boldly lies about others, every situation he was involved in, and then victimizes himself.

This statement has the same effect as the state’s counter-insurgency efforts, regardless of his intention: foolishly calling for others to embrace passivity and act recklessly about state repression is literally accomplishing the same objective that the police attempt to achieve. As the article “Why Misogynists Make Great Informants” argues, aggressive patriarchs do not necessarily have to be state agents in order to destabilize movements in the same way that informants do; this person fits that profile pretty well. “Self-determination” by not doing anything to actively abolish the system and by pretending that the police don’t exist, he insists. To this day, we do not know of any individuals or groups “commanding” others into militancy within the IE. For those who lack nuance, militancy is a tactic that folks pick up out of their own accord and on their own terms; it is not imposed or pressured unto others. In fact, militancy without accountability and consensus is a liability. Militancy is also not an end in itself nor is it meant to establish hierarchies of who is “not down” and who is “more revolutionary”: it is merely a tool among many others that movements have. It could also help to clarify that “security culture” should only be understood as a dynamic set of habits that are context dependent and meant to keep us all safe by minimizing effort and paranoia, not some eternal laws or principles that have to be enforced. With all of this said, we can see how this individual intentionally deflects from their actions and misrepresents situations in order to control the narrative and play victim: classic manipulator and Abuser 101 playbook tactics that we should all recognize and stomp out.

It’s also interesting to see such admonition of militancy when just last year, this same person created a GoFundMe (the link which is no longer up) to supposedly fund military grade ballistic vests, shields, and other protective gear for IE protestors. Is that not militancy, or is it only wrongfully militant when anyone but him does it? More importantly, did the community ever see any of that money? Of course not. With the funds, he purchased a generator meant for “community use” that he very conveniently safeguards for himself. He spent last year defending Jaydee against accusations that she and Josh were suspicious and untrustworthy. Posting his full name and face to his social media as well as videos of his protest gear is the exact opposite of security culture, and what did that get him? A house visit from the feds. He removed his name and face from social media and changed his phone number in response, and yet he says that we should abandon security culture. Anonymity would have protected him from state repression had he proactively engaged with it. How can anyone be an ally to folks on the ground and still make a sweeping statement for organizers to abandon security culture?

The inaccurate suggestion that pigs are just idiots who eat donuts when they are agents of the state who literally carry out strategic, organized, state-sanctioned violence is just copaganda. This person only continues to share more false information and talks out of his ass most of the time; his attempts at detraction and belittlement of real possibilities of state repression reveal that this person does not actually stand for anything or have any actual commitment to long-term struggle. This is yet another example of “radical” liberals posing as militants when they’re nothing more than clout-chasers co-opting radical language and using “revolution” as an aesthetic. Causing harm to multiple people in organizing spaces, just to refuse efforts towards a transformative justice process, to then act high and mighty on social media while giving dangerous advice is proof of people who are simply not interested in their own accountability and continue to be harmful.

If the goal is to engage a transformative accountability process with any of these people, the first and most vital step is already missing: acceptance of the harm committed and self-accountability. As of today (July 2, 2021), none of the demands from Josh and Jaydee’s call out statement have been met. Not even a permanent post acknowledging the call out has been added to their personal or organizations’ social media accounts. As per usual, the deflection and silence show how often harm is dismissed, avoided, ignored, and forgotten. An apology without changed behavior means nothing, just as time passing is never acceptable reparation.

There is much literature on what transformative justice can look like and how accountability processes work, but in case this needs to be explicitly stated: People who cause harm need to rectify that harm by obliging to the demands created by victims – in this case, community members intervening to prevent further harm. Period. There is no “But I didn’t feel I was causing harm,” because what matters is that harm was caused anyway. There is no “I’ll publicly apologize but secretly keep doing the same thing.” There is no “I’ll cry on camera to center my feelings instead of the harm I caused.”

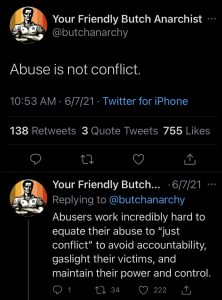

As per usual, this behavior is a consequence of co-optation. In this case, it shows the result of people learning the language of radicalism and transformative justice to then weaponize it and victimize themselves when they are the ones causing harm. The concept and language of accountability is now so far removed from the meaning and usage that originated in transformative justice work. For example, we see people say things like, “So-and-so needs to be held accountable,” when in reality, people should be saying, “So-and-so needs to hold themselves accountable.” Nobody can hold anyone else accountable, and this is why transformative justice processes fail so often: Unless the person who caused harm admits to causing the harm and willingly takes steps to rectify it, there will be no “transformation,” only a shiny veneer of “accountability” that eventually leads to the same person causing similar harm in new spaces. Transformation can only exist in people who acknowledge their harm and actively work to ensure it never happens again. There is no shortcut or magical thinking that wills someone to become different; it’s hard work that begins with the person who caused harm in the first place. Without that personal accountability and actionable steps to do better, a transformative justice process is simply not possible.

This then begs the question: “What do we do with people who won’t take accountability and work towards transforming themselves after causing harm?” From an abolitionist perspective, transformative justice is key when imagining non-carceral and non-punitive approaches to conflict and harm, but there are limitations to these approaches.

Specifically, nothing works unless a harm doer willingly engages in an accountability process; sometimes, that process includes staying away from possible victims until the harm doer can prove they are no longer a threat. Some people who still believe cancel culture exists will say that outing harm doers and removing them from spaces is punishment, but that is simply not true. If someone causes harm, is called in privately by their peers and nothing changes, is called out publicly in hope that the greater community will intervene and nothing changes, the only alternative left is removal. How is it “punishment” to out and remove a dangerous person, but their active harm against others is not? For the people comparing a harm doer’s removal from a space to incarceration, that is an entirely false equivalent for obvious reasons, the primary reason being that they are not incarcerated. They are not being “oppressed” by being asked to go back to their normal day jobs and stay away from organizing spaces. They are not being actively punished and the quality of their lives is not being jeopardized.

As a general rule, most people don’t particularly enjoy conflict: it’s embarrassing to be called in even when it’s done by trusted peers, criticism can elicit a knee-jerk defensive response, and it’s scary to feel that you are disappointing people. Although these reactions are commonplace in response to criticism, they are not conducive to healing conflict. (For the intent and purpose of this piece, conflict here refers to normal, low-level interpersonal conflict, not abuse and harm. The latter are serious and should never be minimized to “just interpersonal conflict,” and anyone who does minimize them is probably someone intent on continuing their own harmful and abusive behavior.) In personal and working relationships, it takes a lot of self-awareness and personal accountability to choose understanding others over nursing your own ego. Lashing out when a homie or your peers call you in is ultimately a response rooted in pride and ego. Thinking you are not capable of or that you are otherwise exempt from causing harm stems from the same place. Nobody is perfect, nor are they “above” any form of constructive criticism or community feedback. Liberation is about collective effort towards self-determination and not about untouchable personalities or fragile egos.

Now, imagine pride and ego mixed in with a hunger for power and control. Now you have egotistical people causing serious harm instead of just interpersonal conflict and refusing to be accountable for their actions. When people show that they care about remaining in a position of social power and coddling their bruised egos more than they care about the people they are in community with, believe their actions. Cries about “cancel culture” are really just classic Abuse 101 manipulation tactics to preserve harm doers’ reputations and public images to stay in power, meanwhile their private behaviors attest to an entirely different person. Cries of “cancel culture” also distract from the harm that was actually caused, instead switching the narrative by victimizing the harm doer in order to keep appearances. People who cause harm and then avoid accountability thrive off of being seen as the victim. These people believe that others – including the people they’ve harmed – need to be understanding of them and their personal traumas, need to coddle their ego and public image by being silent, need to allow more harm into their personal spaces. Zero accountability, zero understanding of boundaries except their own, and all the desire to center themselves in the process. Everyone in this violent, cis-heteropatriarchal, racial-colonial system has experienced some form of trauma at some point in their lives; the issue here is the manipulative weaponization of said trauma during incidents of harm or abuse. As comrades in struggle, we owe each other not just the best of ourselves, but also a shared commitment to grow and learn together instead of refusing ownership of harmful actions.

How can we build the elusive, impractical, nonexistent “leftist unity” with people who refuse to take responsibility for the impact of their actions? What are the aims and goals of building false unities with people who harm and back-stab others? Reducing these tensions to mere “interpersonal conflict” and “infighting” implies that we were all on the same side to begin with, which is not true. Reducing harm that is rooted in violent colonial systems of patriarchy to mere “beef” obscures the real issues at hand by collectively gaslighting us (by making us question ourselves whether incidents of harm and abuse really are just “beef” when they are obviously not). Having “left” tendencies does not mean everyone has the same goals, nor that we all agree on how we should achieve them. It certainly doesn’t mean we should ignore harm for the sake of our “leftist” social clubs. Welcoming harm doers and people who avoid accountability into revolutionary spaces does the literal opposite of constructing a community that doesn’t depend on police, politicians, or their shitty joint legislature; instead, it shows just how invested we still are in maintaining abusive social dynamics that inevitably recreate oppressive social structures.

Treating activism as a social scene leads to investments in pre-existing social conditions: public image and respectability, power and hierarchy, cisheteropatriarchy and whiteness. As anarchists cultivating autonomous spaces, how do we allow people – especially disruptive white people in primarily Black and brown spaces – to appoint themselves as leaders and make themselves indispensable to our movements? It’s inconsistent with horizontal organization and leaderless movements, but entirely consistent with clout chasing and hierarchy. How do we take seriously people who claim to be doing “illegal shit” for street cred while blasting their full names and faces on social media when we should be dismissing them as fed magnets? How do we trust with security the people who care more about being seen as activists instead of keeping our comrades and spaces safe?

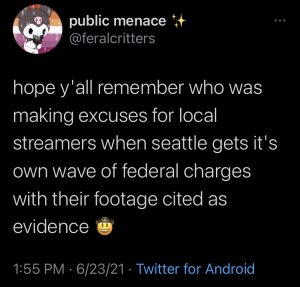

Cult of personality activism isn’t new but is definitely on the rise with the prevalence of social media. There really is a playbook for “activist-y” types: people who put “activist” in their social media bio like it’s a profession, hobby, or identity; people who post themselves and others at actions and/ or doing illegal shit; people who tag the organizations and groups they belong to in their bios. Not only is it a gross manifestation of the need for attention and social clout, it can actually be really dangerous – real life, end your shit dangerous. It sounds dramatic, especially to people who aren’t involved in clandestine activity. Sure, perhaps tagging the nonprofit where you do above-ground work isn’t going to get you caught up, but some clout-chaser posting your mutual aid group on their bio is a potential security threat: publicly posting who you work with can alert authorities that can infiltrate the group. And no, it’s not the mutual aid initiative the feds are after, necessarily; it’s the juicy details about your comrades planning a demonstration or vandalizing property at an action. In fact, contemporary policing is now preemptive instead of just reactionary; in other words, the state has long studied autonomous movements and has begun to identify “early” signs of disorder, whether or not they are actual “threats.” For instance, police seek to crush dissent before it generalizes to the extent that pigs target mutual aid groups and other community building efforts to instill fear into growing movements. If this still sounds dramatic, we invite you to investigate past experiences to see how Black Lives Matter organizers were targeted and murdered after the Ferguson protests in 2014. In the wake of protests after George Floyd’s murder in 2020, organizers were and are still being targeted by the state. Winston Smith was just murdered by undercover cops after posting a video calling for more militant action against police violence. The Black Panther Party (and other Black liberation groups) is perhaps one of the more famous examples of infiltration leading to death and dissolution; revolutionary Black elders are still imprisoned as we speak because of this. Anyone who is seen as a threat to the state and racial capitalism is dealt with accordingly, and proof of this is sprinkled all throughout history. To not know this history is one thing, but to actively ignore and dismiss the possibility of violent repression is to put our loved ones in unnecessary danger. Our enemy is the state and although it is certainly not invincible nor should we overestimate its capabilities, we should take our cues from those with direct experience combating state repression and the collective knowledge cultivated by anti-repression efforts across Turtle Island.

Again, for the people not involved in underground organizing, security culture might not be a necessary means to achieve their goals. But to the people doing clandestine work, it can be the difference between life, death, or imprisonment. The point is that people should explore their role in social movements and engage with whatever level of activity they feel comfortable doing; for some, this means exploring militancy or riskier forms of organizing that are necessary for community liberation. Security culture was literally invented to minimize these risks and offer some form of protection; it is meant to keep you, your comrades, and entire movements safe from co-optation and dissolution. As we noted earlier, any person who shows even one sign of defiance against the system – whether that is by doing something as harmless as feeding the homeless – puts a potential target on someone’s back. Any “activist” worth their shit understands that this work comes with risk, and whether it is their own risk or not, should care to protect their peers if they’re actually an “ally” to radical work. Disregarding anonymity and security for social clout is irresponsible and selfish, and shows how just one grifter, clout-chaser, starry-eyed liberal, and the like can end individual lives, larger organizations, and entire movements. People with these tendencies need to be taken seriously as the threats they are.

Harm doers who refuse accountability need to understand that nobody owes them forgiveness, especially when the behaviors that led to a call out have not changed and will not change in the foreseeable future. Nobody should be expected to be Jesus Christ who “turned the other cheek” after getting whipped across the face. If someone unrepentantly causes harm, actively tries to hide it, and then continues to cause harm, people have every right to keep themselves and their loved ones safe by keeping far fucking away and warning others of harmful behavior. It’s not “punishment,” it’s a matter of boundaries and safety. Actions have natural consequences and harmful people are not entitled to the communities and spaces they have actively harmed. We all have the right to self-defense and safety from all those who wish us harm, whether they are state or non-state agents.

Still, there will always be people who sympathize more with harm doers than the people harmed: “But they’ve never acted that way towards me! But why couldn’t they be privately accused instead of publicly outed? But why do they need to be canceled instead of rehabilitated?” And to those people, we welcome you to take the initiative in rehabilitating people who aren’t invested in their own transformation and reject accountability entirely, since this seems to be an area of interest for you! Did this letter make you angry because it “called out” people it shouldn’t have, or because you don’t think call outs have a place in transformative justice? If you don’t want people to be “disposed of,” then you should take the initiative to head accountability processes and ensure harm doers meet the demands made and actually change. Otherwise, you’re not just a morally superior sympathizer, you’re complicit in harm as well as the perpetuation of a culture that accepts it, which is far more insidious than individual instances of harm. In this patriarchal society, r*pe culture is not just about actions committed but also – as the name implies – society-wide norms and values that enable violence and silence survivors. When people refuse to be responsible for the harm they cause, they are destined to keep doing it. There is no magical fix to harm or people who cause harm, and all of the people crying about disposability and cancel culture never even attempt transformative or restorative justice work because they have no better solutions. Siding with harm doers because you empathize more with them than the people they harm doesn’t make you more radical or more moral, it makes you complicit. We must not be innocent bystanders to incidents of harm any longer.

As a community, we need to be willing to tell unrepentant harm doers that we fucking see and remember them: even if they stop posting for a week waiting for their call out to blow over, even if they delete posts and pretend nothing happened, even if they change their scene and move to a different place, we will remember how they willfully harmed the people they were supposed to be in community with and purposefully tried to slip that harm through the cracks. Today, it will be specific people in our own communities stealing funds, posturing as saviors for Black and brown people while harming them, using organizing spaces for personal clout. But it isn’t just an individual issue or a new one: this is a playbook that happens across time and place and will continue doing so if we don’t learn to spot these patterns early and address them immediately. Organizers involved in transformative justice work have been screaming into the void about this for much longer than we have. We keep our communities safe by recognizing grifters, abusers, and manipulators and shutting down bullshit as soon as we see it. By cultivating a culture in which we prioritize the safety and security of ourselves and our comrades – be it against feds, snitches, or abusers alike – we make it less likely for our comrades to experience harm or our movements to be co-opted by walking safety/ security threats. Anything else shows that we care less about the safety of our comrades than we do about maintaining a status quo that is not designed to keep marginalized identities safe in the first place. Anything else allows rot to take root in our spaces and suffocate us the same way the state already does. If harm and unrepentant harm doers are inevitable because “we live in a society,” the very least we can do is take responsibility for our inadvertent contribution to this culture and try our best to snuff it out once and for all.

Solidarity and strength to all survivors and communities who are harmed and silenced. The axe forgets, but the tree remembers.